Knee Valgus During the Squat: Dangerous to the ACL, or Conducive to Glute Activation?

Knee Valgus, also known as knees “caving inward” during a squat, is a common fault among athletes and gym-goers that risks the health of the knees.

This movement fault is commonly thought to be the result of poor glute involvement and tight inner thigh muscles.

It has long been thought that his movement “fault” must be avoided at all costs because of the risk of knee damage to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). However, a recent study may challenge this line of thinking.

A 2024 study by Chiu et al. found no significant differences in injury rates between lifters who squatted with a valgus knee position and those who let their knees track over top of their toes. The study also found the glutes to be MORE activated when the knees caved in during the squat, rather than with the knees tracking over the toes as previously thought.

While this is a recent finding and this is only one study, it is starting to get more attention. Dr. Layne Norton, who has a PhD in nutritional sciences and is a powerlifter who has squatted over 600 lbs, recently did a synopsis of this study on his YouTube channel. You can check that out below.

Let’s dive into what knee valgus movement is, how it could be potentially dangerous to your knees, the role of glute activation, what new research is finding, and what it all means for you and your squat training.

Knee Valgus During Squats

What is Knee Valgus?

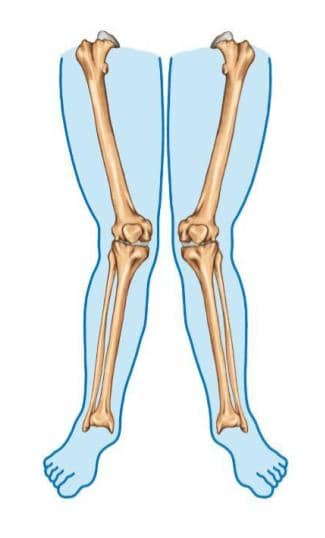

Knee valgus refers to the inward movement of the knees, often giving a “knock kneed” appearance. It is often observed during exercises like squats, lunges and jumping.

Knee valgus can be caused by a variety of factors, including:

- Weak hip abductors

- Inhibited glute muscles

- Tight inner thigh muscles

- Poor motor control

ACL Injury Risk and Knee Valgus

One of the common concerns associated with knee valgus is its potential contribution to ACL injuries.

The ACL is important for:

- Preventing forward movement of the tibia

- Providing rotation stability

- Maintaining overall stability of the knee

Injuries to the ACL typically occur in sports that involve a lot of cutting, deceleration and quick change of direction when sprinting. When the ACL is injured, the athlete’s knee will typically cave inward.

So it is understandable why it has long been thought that the knees caving in during squatting is dangerous. Research has suggested that excessive knee valgus increases the risk of ACL damage because the valgus alignment places stress on the ligament.

The Role of Glute Activation and ACL Risk

The glutes stabilize the hip and prevent excessive adduction (inward movement) of the femur. Without proper glute activation, the body may rely on weaker muscle groups, such as the adductors or quadriceps, to stabilize the knee, increasing the likelihood of a valgus knee collapse. When the knees cave in, the glutes are “off”. When the knees track over the toes, the glutes must be working.

But Chiu’s study found quite the opposite to be true.

The Study and its Findings

This study looked at the squat biomechanics and muscular activation patterns from two major styles of squatting, knees out (lateral rotation) and knees in (medial rotation). The study aimed to clarify how voluntary hip rotation during squatting impacts squat performance, joint health, and glute muscle recruitment.

The participants performed squats on a force plate from a bench with either their knees out or caved in.

They found that squatting with knees out elicited greater response from the adductor muscles (inner thighs) while squatting with a VALGUS collapse elicited GREATER glute activation. What?

Valgus knee collapse is usually avoided for fear of damaging the ACL, but the study found that the force of the knees collapsing during the squat was not great enough to cause injury to the ACL.

So, to sum up:

- Knees caving in during a squat was previously believed to be a sign of weak glutes.

- The study found that knee valgus may not be a result of poor glute activation

- More glute activation was seen in the “knees in” group compared to the “knees out” group

- It was previously thought that knees in squatting would put too much stress on the ACL.

- The study found that the stress on the ACL during valgus knee squatting was not noteworthy enough to cause concern. There is lower risk of ACL injury than previously postulated.

Conclusion

It was surprising that the researchers found more glute activation in knee valgus squatters. Most exercises that target the glutes are “knee out” exercises like many various forms of hip abduction muscles like band walks and side lying clams.

So what do these findings mean?

First off, this is just one study. More research is necessary. And this study does NOT suggest that you should change your squat mechanics to a valgus knee position. But it should really highlight how there are different ways to perform exercises and there is not one uniform, cookie cutter shape or form that you have to mold yourself to, lest you risk damaging your joints.

Another thing to keep in mind is that even though squatting with the knees caved found little to no risk to the ACL and elicited greater glute activation, you should still allot time for training your glutes exclusively.

Exercises like the barbell hip thrust, single leg squats and Romanian deadlifts can target these muscles and improve their ability to control knee alignment during lower body movements. I usually have my clients utilize booty bands on various squats and hip thrusts to engage the Gluteus Medius prior to training the squat.

Coaches and athletes should focus on developing strong, functional glutes to enhance movement mechanics and minimize knee valgus faults in dynamic movements. Additionally, strengthening the hip abductors and improving core stability should be a focus as well.

In athletes who are particularly prone to knee valgus, biomechanical assessments and individualized corrective exercises can be helpful in preceding long term damage to the knee joint and ACL

Training Implications

If you are going to tweak your squat form, you should stay at lower weights for a few training sessions to allow your tissues to adapt to the new way of squatting. You should not change your squat and then throw a lot of weight on the bar. This could get you injured.

Here are the major things to consider for quality squat training:

- Improve range of motion – this is most important. Try to improve your range of motion gradually working down to a squat that is parallel or below.

- Increase repetitions – start with sets of 5 reps and work up to 10 reps per set. This will help you determine what repetition range allows you to feel your glutes and quads the most.

- Add weight gradually – slowly increase the weight. Adding resistance to the bar is important but sometimes when you add too much weight too quickly, it can alter your squat mechanics. Be patient. It takes time to develop strength and build muscle.

- Increase set volume – add sets to your weekly work load. Training volume is key. If you want to see consistent improvement, you should be shooting for sets of 6 – 10 total sets per week.

Keep these principles in mind. Improve technique, practice often, progressively overload and watch your squat improve over time! Good luck!

Key Takeaways

References:

- Chiu LZF. “Knees Out” or “Knees In”? Volitional Lateral vs. Medial Hip Rotation During Barbell Squats. J Strength Cond Res. 2024 Mar 1;38(3):435-443.